Imagine spending all your time collecting crosses, stakes and holy water only to be mutilated by werewolves. Still, buying one more clove of garlic will make you a little bit safer from Dracula. If we sink too much of our budget in one program, we have to neglect others. Sacrificing life for money at all costs is indirectly sacrificing quality of life and other lives to save specific lives. Those are all costs as well, and money is just a stand-in for the resources that must be sacrificed. Increasing one form of spending too much will cannibalize the rest of the economy and make everyone worse off. The big question is where that line is drawn. I don't know how many times I've heard people speak out against institutions they claim puts a price tag on human lives. Both anti-corporation and anti-government activists accuse their foes of valuing money more than humanity.

I don't know how many times I've heard people speak out against institutions they claim puts a price tag on human lives. Both anti-corporation and anti-government activists accuse their foes of valuing money more than humanity.

When a car company declines to install a safety device, that's putting a price on human lives. During the 2008 debates Sarah Palin declared a national health care program would use "death panels" to decide which lives are worth saving.

But coming at these issues from the economic mindset, the real scandal would be car companies that install every safety device possible and the horror of a national health care program would not be in having death panels, it would be in not having them.

This principle of only saving lives if the cost is low enough is well accepted with most people, they just don't realize it. It takes three different forms I will focus on in decreasing order of popularity.

Risking lives to save more lives

At the cost of a few lives, you will save many more lives.

This is straight-up utilitarianism. If three hundred people have a deadly disease that will kill them in less than a week, and you have a drug that will cure it outright but also kill two or three of the patients, you give it to them.

This is a no-brainer. At the cost of a few lives you have saved hundreds. You're exposing people to a little risk to avoid a bigger risk. This is the idea behind vaccines, airbags, triage and a lot of other things. You're trading risk for risk, and on the average you win. There is little controversy when people properly understand what the stakes are.

Risking lives to save quality of life

At the cost of a few lives, you will improve the quality of many lives.

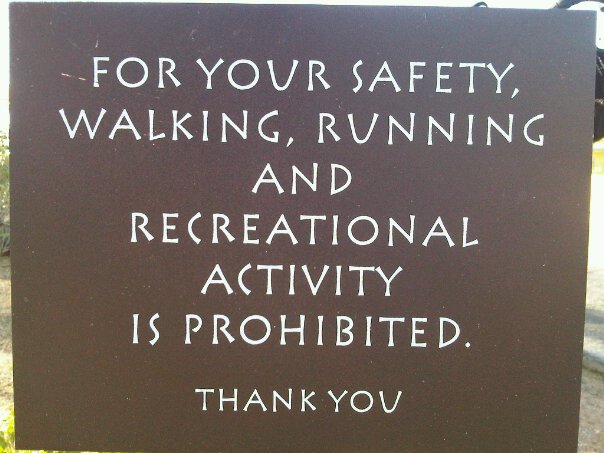

There are things that anyone can do to lower their risk of a specific cause of death. As oncologist Dr. David Gorski wrote, there's a lot of danger in riding an automobile, playing sports and even swimming. Foregoing these activities will increase safety, but is it worth it? What about eating salads for every meal, wearing a helmet at all times and never leaving the house?

Some of these actions will expose the actor to other risks, such as a weak body, malnutrition or poverty, but the main factor is the quality of life. Lenore Skenazy writes about how the obsession with child safety is ruining childhood on her blog Free-Range Kids. This principle was the focus of my recent piece on invasive searches for airline travelers. Sure, it may eventually save a few lives, but at the cost of harming the quality of millions of lives.

Now some people do think the harm of the TSA searches is worth it for the extra protection we get. I must ask, are they really disagreeing with the principle, or just the price? What if the searches were more invasive? I imagine terrorists would have a difficult time getting weapons on a plane if all passengers were naked and had no carry-ons. Would that cost be worth it too? If not, then they clearly agree with the principle I'm presenting.

Risking lives to save money

At the cost of a few lives, you will save a lot of money.

This is where people start to back away. Philosopher Peter Singer recently wrote that because most people can agree that extending someones life a month for the cost of millions of dollars may not be worth the price, they are therefore open to the idea of rationing health care:Remember the joke about the man who asks a woman if she would have sex with him for a million dollars? She reflects for a few moments and then answers that she would. “So,” he says, “would you have sex with me for $50?” Indignantly, she exclaims, “What kind of a woman do you think I am?” He replies: “We’ve already established that. Now we’re just haggling about the price.” The man’s response implies that if a woman will sell herself at any price, she is a prostitute. The way we regard rationing in health care seems to rest on a similar assumption, that it’s immoral to apply monetary considerations to saving lives — but is that stance tenable?

Milton Friedman made a similar point when asked if its ethical for an automobile company to avoid installing a cheap safety device. He argued that he doesn't know if the cost of the device was worth the limited amount of safety it gave, and it should be up to the customer to decide how much safety they are willing to pay for. At the heart of his response, Friedman said:Nobody can accept the principal that an infinite value should be placed on an individual life.

So in effect, arguing that a company should install a safety device to combat a specific amount of risk is haggling the price of a human life. It is not rejecting the principle.

Never assume your current level of safety is optimal, so that increasing risk is out of the question.

Say there was a device that made your home 100 percent safe from asteroids. Any space-borne rocks that hit your home will be safely deflected each and every time, and at a cost of $12,000 a year. Of course, asteroids do not pose a substantial risk to the public; a person's chances of being injured or killed by an asteroid in a given year is one in 70 million.

But say you already have the device in place and decided to discontinue it's use. You'd save yourself $1,000 each month, but you'd have to accept the principle that you are increasing your chances of an unnatural death in order to save money. You can't get around this fact, and that's what I mean by not assuming your current level is optimal. If it's right to avoid paying a big fee for a small amount of protection, its no different to cut big costs in exchange for a small increase in risk.

That was my point when I wrote that it doesn't matter if hiring more nurses, teachers or soldiers will improve outcomes if it comes at too high cost. It's possible we have too few nurses, teachers and soldiers, and it's also possible we have too many. We should always be open to changing the number we have, even if it means spending more money or lowering our health, test scores or national security.

It's also important to remember the opportunity cost of protecting ourselves from one threat could leave us vulnerable to another. I have added emphasis to something Carl Sagan wrote in The Pale Blue Dot:Public opinion polls show that many Americans think the NASA budget is about equal to the defense budget. In fact, the entire NASA budget, including human and robot missions and aeronautics, is about 5 percent of the U.S. defense budget. How much spending for defense actually weakens the country? And even if NASA were cancelled altogether, would we free up what is needed to solve our national problems?

It's clear that its worth saving a human life when the only cost is the effort of throwing a life preserver overboard, and not worth saving at the cost of all the resources of an entire continent. The extremes are easy, but making decisions at the margin is tough. Finding the optimal point is beyond tricky: it's impossible. No one can discover the value of an unspecified person's life, and any number they come up with will be arbitrary.

Protecting lives comes at a cost, be it in terms of sacrificing other lives, the quality of life or money. This is a single principle, not three separate principles, and one must accept or reject them all.

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

We must put a price on human lives

Labels:

Carl Sagan,

economics,

Ethics,

Health care,

Milton Friedman,

Opportunity Cost,

Philosophy,

Risk,

skepticism,

Triage,

Utilitarianism

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Figured it out.

ReplyDeleteLike I said, Its easy to put a price on your own life or even those you don't know. It's much more difficult to put a price on your friends lives and really follow through if the time ever came.

Its a wonderful argument your making, I just don't think that most people would be able to price out others lives. We have an all volunteer military, its the individual soldier that has decided the cost for his or her life, at the moment he signs the contract.

And your right a simple google search came up with sound proof the holy water does not work on werewolves!

ReplyDeletehttp://ilovewerewolves.com/holy-water-vs-werewolves/

(Beware I am certain the person that wrote what's on the other side of that link is insane.)