As a practicing journalist, there are strict rules I must follow for the purpose of neutrality. I can not publicly endorse political candidates, parties or movements. I can't march in a protest or place campaign bumper stickers on my car.

It's not just politics. Earlier this year I was invited to join

Rotary International, and I knew I had to turn it down. My editor confirmed this; it would be a public endorsement of the group and I wouldn't be able to cover its events with what appears to be a fair viewpoint.

Like all conflict of interest issues, it's not a matter of if I could remain neutral. It's a matter of the mere appearance of neutrality.

I don't like labor unions at all. I interviewed the fire fighter's union rep in a recent story then saw him at a scene a few days after it was printed. I asked him how it came out and if I represented his side fairly, and it felt genuinely good when he said I nailed it. Clearly, I have some ability to set my views aside.

But how would he have read it if he knew I think his organization is a labor cartel that conspires to take advantage of the public with oligarchy power, fearmongering and flawed reasoning? His interpretation of my wording may have changed and the same story would have angered him. My paper's reputation would have been damaged.

That's why we have rules, you see. It's easy to understand. As a journalist, I give up certain rights in order to do my job correctly. It's not a legal requirement, it's a performance requirement, and I agreed to it when I chose this line of work.

But

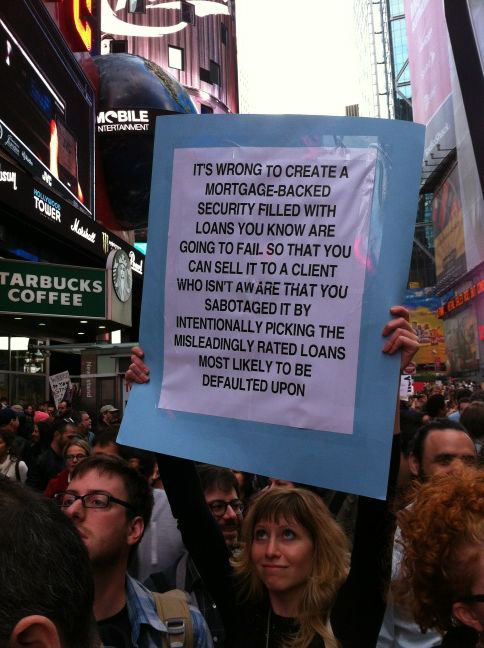

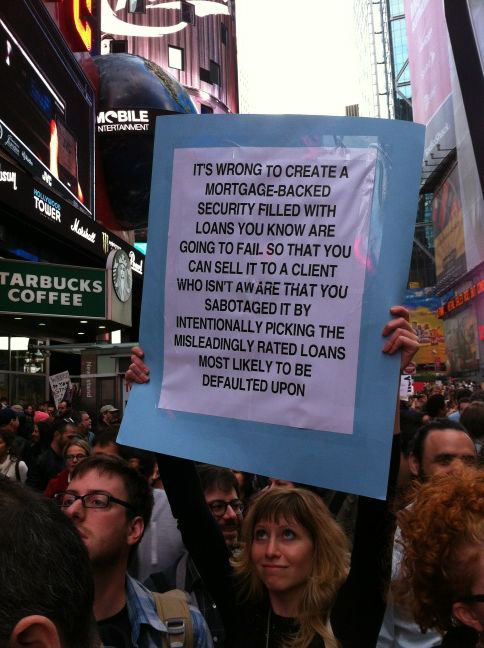

Caitlin Curran, activist and freelancer for a show broadcast on NPR, doesn't understand this basic journalistic rule. She got caught protesting in Occupy Wall Street, tried to turn it into a story and got fired for it. She did not, however, learn anything from the experience, as can be demonstrated by her

dishonest statements in an interview with Bob Garfield from On The Media.Curran's silly defense, which Garfield did not let her get away with, was that:

*She just wanted to check it out.

*She wasn't really participating.

*She only held the sign for a little while.

*Her political sign wasn't political.

*Occupy Wall Street isn't political.

*This happened in her personal time.

*The rule is wrong and journalists should be able to express their views in public.

Curran just doesn't get it, and from the

comments section in the liberal blogosphere, a lot of other people don't get it either. I can see a minor defense against a similar incident when the host of an opera show was eighty-sixed for being an anti-war spokeswoman. It's not as blatantly wrong as what Curran did, but once again, the

sympathetic far left Internet squad just doesn't get it.

I have to walk a fine line. I was a newspaper editor in 2008 and the beginning of 2009 and some of my editorials are online. I was also the op/ed editor of my college newspaper my senior year and some of my political articles from that time are still online. My political views can be tracked down.

But I still make an effort. I was the president of a skeptics group when I was between journalism jobs and now that I'm working again, I'm not a member of any of them. I told my editor when I was offered a position to speak at TAM 9 and he gave me his blessing. Even still, I follow a strict policy about what I do, what I say and what I post here on YH&C.

I fully believe that I can write fairly on topics despite having a lot of strong views. The trouble is convincing my readers that I can pull it off. That's beyond my control, and that's why the proper thing to do is to keep them guessing.

As a journalist, I keep a single allegiance in mind. It's not to the politicians I interview. It's not to the publication that prints my words, nor is it to the public that reads what I wrote. My loyalty is to the truth; the actual events that occur in the world. It's not to any other idea or entity. Anything less is a betrayal of reality.

Read more...

Like most aspiring pundits, I enjoy Googling things just to make myself upset. That's why I just ended up doing a news search just to see what Michael Moore has been up to. I clicked on exactly two articles about him and the contrast was beautiful.

Like most aspiring pundits, I enjoy Googling things just to make myself upset. That's why I just ended up doing a news search just to see what Michael Moore has been up to. I clicked on exactly two articles about him and the contrast was beautiful.